Canon Noel Duckworth, the son of a Yorkshire vicar, became a coxswain famous for remarkable achievements on and off the water, his career inseparably linked with Jesus College, Cambridge University and The Boat Race.

Arriving at Jesus College in 1931, Duckworth’s rowing career almost ended before it had begun. On his very first outing as a cox, he misjudged his steering, knocked ten feet off the end of the boat and sent the crew into the river. Fined £10 for the damage, he decided to stay on in the Boat Club, later remarking that he intended to “get my money’s worth”. That moment of determination marked the start of an extraordinary rowing career.

Wins in The Boat Race, Henley Royal Regatta and the Olympic Games

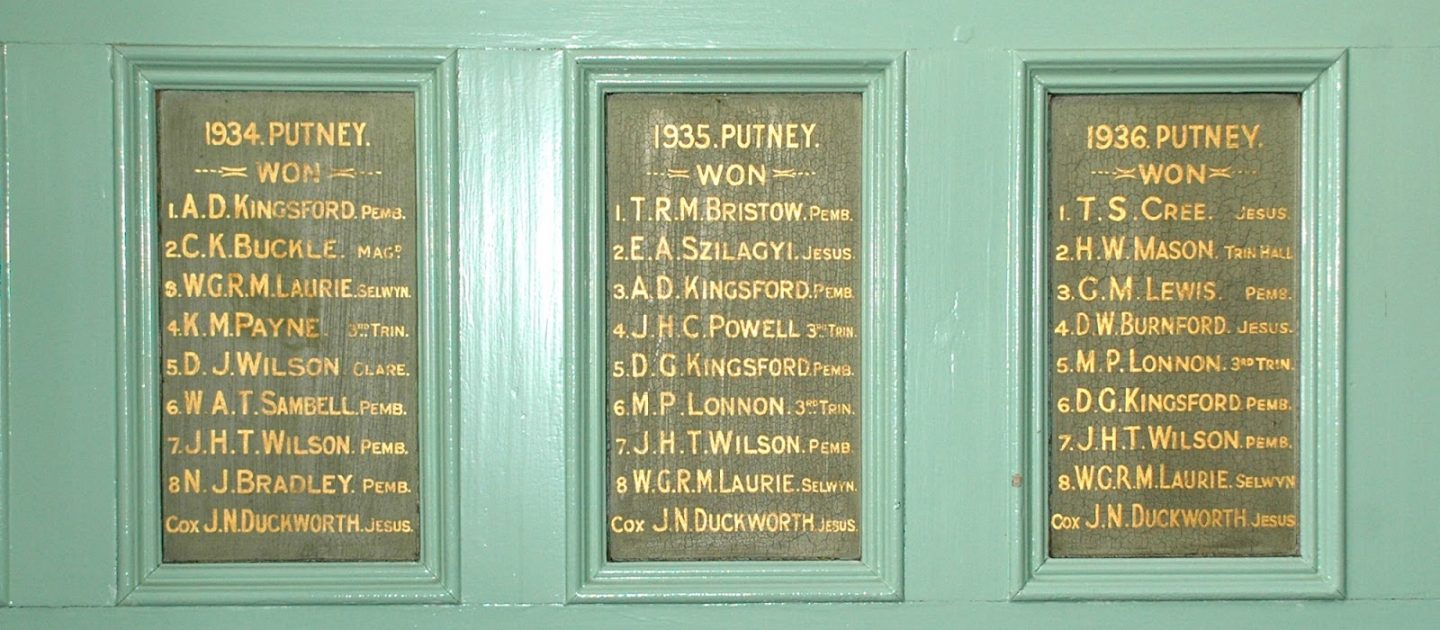

By the mid-1930s Duckworth had established himself as one of the finest coxswains of his generation. From 1934 to 1936 he coxed Cambridge to three consecutive victories in The Boat Race, during the middle of the University’s record-breaking run of 13 wins in a row. The 1934 race was won in a then record time, a year that proved to be a high point in Duckworth’s career. In the same season he coxed Leander Club to victory in the Grand Challenge Cup at Henley Royal Regatta, also in record time, and as part of the Jesus College crew to success in the Ladies’ Plate – an exceptional treble.

His achievements on the river extended beyond Cambridge and Henley. Duckworth went on to cox the Great Britain eight to fourth place at the 1936 Berlin Olympics, further cementing his reputation as one of the outstanding coxswains of the era. That same year, however, he chose a different calling. Ordained as a priest in 1936, he joined his father and two brothers in Holy Orders within the Diocese of York; like him, both of his brothers later became Canons.

Wartime arrives

The Second World War interrupted his clerical career. At the outbreak of war in September 1939, Noel was appointed Chaplain to the 2nd Battalion, Cambridgeshire Regiment and was sent to Malaya in 1941. In January 1942, the 2nd Cambridgeshires and others were defending Batu Pahat on the west coast. They were ordered to withdraw as they were in danger of being cut off by advancing Japanese forces. As a non-combatant, Noel should have been the first to go but he and two doctors chose to stay with those wounded who could not be evacuated.

Duckworth’s biographer, Michael Smyth, puts forward a fascinating suggestion as to why Noel was not killed:

When Noel was captured with the wounded soldiers one of the doctors who had also stayed behind attested, “I firmly believe that Noel’s fame as a rowing man saved all our lives” because a Japanese officer recognised Noel. This story is given some credence by the fact that a Japanese crew from Tokyo University participated in the 1936 Berlin Olympics, as well as Henley prior to that, so it is likely that Duckworth was known to them. Furthermore, of the Japanese Divisions used for the invasion of Malaya, one ‘the Imperial Guard’ traditionally recruited its officers from Tokyo University!

Noel’s obituary in The Times noted one of his vital skills:

Duckworth was one of those small men with a giant personality. The skill which he acquired in getting the best out of his oarsmen by exhorting, cajoling, and if need be, verbally castigating, he later employed during the bleak years in (prisoner of war camps) both to sustain his fellow prisoners, and to extract those small concessions from the Japanese guards which were so vital to survival.

After the fall of Singapore to the Japanese, Noel was moved to Changi Gaol and in 1943 was sent into Thailand and Burma on the construction of the notorious Burma Railway. There he tended hundreds upon hundreds of men dying from disease and starvation. Over 90,000 Asian civilians and 16,000 Allied POWs died in the building of the railway.

On the completion of the railway, Noel again chose to stay behind with those judged too ill to move back to Singapore, his indomitable spirit having the same inspirational effect on the men to that which he had at Padu. He was one of the very few who lived to return to Singapore in April 1944.

A career in peacetime

After the war he returned to Cambridge as chaplain of St John’s College from 1946 to 1948, before working in the Gold Coast (modern Ghana), where he became Canon of Accra. Following Ghana’s independence in 1957, he returned to Britain and took up a post at Pocklington School in Yorkshire. His connection with Cambridge rowing was renewed in 1961 when he became chaplain of the newly founded Churchill College. Almost immediately, he set about establishing the College’s Boat Club. To this day, the club commemorates him annually and always names a boat “The Canon” in his honour.

Duckworth remained closely associated with the Boat Race long after his competitive career ended. He later commentated on the race for the BBC and, in 1959, was featured on the television programme This Is Your Life. His remarkable story was told in full in Michael Smyth’s 2012 biography, Canon Noel Duckworth: An Extraordinary Life.

From a disastrous first outing at Jesus College to record-breaking victories on the Thames, Canon Noel Duckworth’s legacy is firmly woven into the history of Cambridge rowing and the Boat Race itself.